This issue examines the possibilities of an ethics based on the STA way of looking. Some of these ideas may seem absolutely crazy, but we think there’s a clear logic behind them. Stop and consider, and make up your own mind.

The myths of Ancient Greece are all the rage. Just as George Bernard Shaw a century ago used the story of Pygmalion to skewer the English class-system, so novelists are now re-furbishing Homer, Hesiod and Euripides to examine current issues of gender and identity.

But other stories of the same vintage are not so popular as they were. The world-view – STA – I think and write about takes its name from the Book of Job. This tale has only been preserved because it was incorporated into that miscellany of laws, letters, legends, poetry and prophecy now known as the Bible, but these days it suffers from the association. Some folk insist every syllable must be true because it is the Word of God; others revile it as the propaganda of an oppressive, obscurantist Establishment. Probably few in either camp actually read Job. The original tellers, spinning their tale around a night-fire, would be mystified. It’s a story: no more factual or despotic than the novels of George Eliot or Elif Shafak but, like them, a story with a message (or two).

Here, very briefly, is how it goes. One morning over coffee, God and Satan are shooting the breeze when the talk turns to Job, a hugely successful stock-breeder with a big family in Uz. He is a pious, worshipful man. God preens at the thought of his devotion, but Satan says he’s only in it for the cash, and that all his pretended piety would dissolve the moment he had a lick of bad luck. God (who is not, in all honesty, a very nice person) agrees to let Satan torment him as a test. Suddenly Job’s wealth vanishes, his family are killed; he himself is plagued with diseases, boils and talkative friends. After a while his patience wears out and he screams ‘IT’S NOT FAIR!!!’ or, in the language of the King James Bible, ‘let me be weighed in an even balance, that God may know mine integrity’.

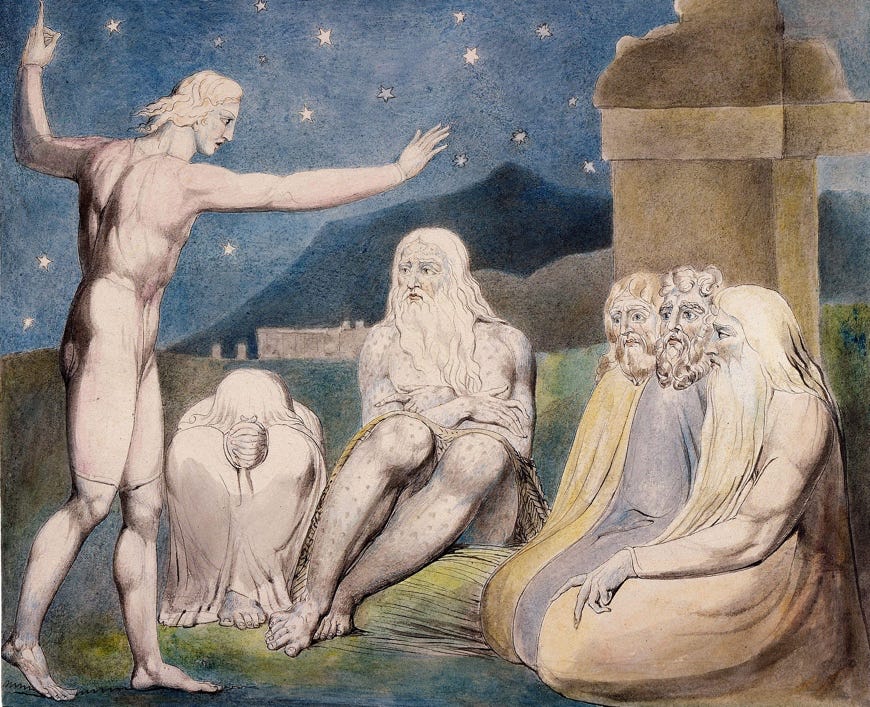

At this point, someone called Elihu (pictured at the beginning of this issue) pipes up. He’s been listening to Job and his pals chuntering on about justice and, with the chutzpah of youth, tells them they’re all wrong. Elihu offers a different perspective. ‘Stand still and consider the wondrous works of God.’ (‘Sta et considera miracula Dei’) The cosmos is the cosmos and is not subject to their wishes. Before Job can say a word, God Himself (and it is a very, very Male Representation of the Divine) proves Elihu’s point with a furious assertion of his own power and Job’s snivelling impotence. ‘Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the Earth?’ God doesn’t care about ‘fairness’. His actions are their own justification; He is God, the Ultimate Everything. After four chapters of Almighty trash-talk Job is beaten into submission and acknowledges ‘things too wonderful for me, which I know not’.

Unappealing as God seems, there’s no getting away from the essential truth of the tale. The Big Thing – whether it be a divine personality or a purpose or a mindless randomness – exerts final power over us and our piping protestations do not count for much. When reality bullies us, shouting ‘It’s not fair!’ at the skies doesn’t work.

This is the root of Job’s misunderstanding; he thinks he knows how the universe works: that when he does A, God will automatically respond with B – a tick-tock, garbage in garbage out, button-pressing, mechanistic view of cosmic order. Reward and punishment; tick-tock tick-tock. This is how he would run things and, like so many people, Job imagines that God is essentially a beefed-up version of himself. What Job regards as Cosmic Justice is, in fact, his own business practice, a trader’s agreement from a regulated world of contracts between equal parties. He expects to do deals with the universe. He assumes that his personal attributes must be those by which everything can be understood, that the cosmos is a book written in his own language. He would not suppose that a cow or a whale or a daffodil could comprehend the workings of the universe – they plainly don’t have the requisite skills, but he is a human being, better still a man, so he thinks he does.

But finally, Job is overwhelmed by divine indignation. ‘I repent in dust and ashes,’ he weeps. Dust and ashes is, of course, the destination for each of us individually, and likely to be our collective fate too unless we learn his lesson, but puffed up with mega-giga-tera-bytes more knowledge than a bronze age cattleman from Uz, we don’t seem in the mood for humility. Anyway, that’s a subject I’ve addressed elsewhere, so for once I shan’t repeat myself. Instead, I’m going to enquire where we derive our ethical values, including justice.

Job’s reward & punishment morality runs through most religious traditions – ideas of karma, of heaven and hell. We have no reason to believe this other than scriptural say-so. Nothing in our own experience suggests that the good end happily and the bad unhappily. Justice and the closely associated notion of rights are cultural concepts, ideas we’ve invented. They are obviously useful in establishing social rules, but they do not reflect necessary reality. Natural justice is as unreal as natural candyfloss or natural chess.

‘Nature, Mr Allnutt, is what we are put in this world to rise above,’ says Katherine Hepburn in The African Queen. Ethics is seen as guidance to overcome nature. We are thought to be superior to the rest of creation and demonstrate the fact by distancing ourselves as far as possible, like a lottery-winner going all posh.

But as all ethical systems are culturally determined, they vary from place to place and age to age. If there is some common ground – ‘the Golden Rule’ has appeared all over the world – there are also deep divergences. Aztecs, Inuit, Vikings, Ancient Greeks and chartered accountants in Reigate are likely to have different standards of behaviour. Pensioners and teenagers go their separate ways. What seemed proper 1000, 100, 10 years ago may not be acceptable now. Some may claim that their ethics are mandated by divine decree or pure reason, but adherence to these authorities is itself a cultural choice. There can be no absolute justice so long as it depends on the judge’s upbringing.

So, if all ethical systems are no more than local bylaws, what do we do? We can follow the ever-changing moral fashions; when we’re in Rome we can do as the Romans do, but only out of polite conformity. Is there no firm ground to stand on? Might there perhaps somewhere be a deeper-rooted ethics, whose origin predates the divergence of cultures and nations? A pre-social ethics?

STA privileges nature over the social constructs that dominate daily life. Perhaps, instead of copying Job and projecting our cultural values on to the universe, we could reverse the process and ask whether the bedrock foundation of nature can give us moral guidance? Of course, there is no morality involved in the actions of goats or bacteria because these creatures lack the reflective intellect that can invent morality. But we need some guidance in our public and personal lives so, with society febrile and changeable, STA counter-intuitively suggests finding the roots of our morality in the amorality of nature.

You may already have spotted the great obstacle, like a landslip in the road, that this route faces. If we are looking for an ethics that is not merely derived from local, social fashions, and if evolution shows that there is no categorical difference between species, we need to find something that will not only work for us, but is already observed by tigers, rhododendrons, skylarks and whelks. This sounds

☐ ambitious

☐ quixotic

☐ stupid

☐ insane

(tick all that apply) – and it may be, but let’s stand still and consider before we judge too severely.

As all living things are related, evolved over billions of years from the same primordial beings, it might not be surprising if we found principles of behaviour in common, but since every creature and every circumstance is unique, these could never be precise or prescriptive. We must tread lightly and carefully. But though no principles can dictate our actions, they may perhaps inform them. I am not expecting to find consistent behaviour from clams, lilies, elephants and slime-moulds – they all have different ways of achieving their needs. But there may yet be consistent principles underlying those behaviours…

And so, I have unearthed these four principles which it seems to me could, with a bit of squinting and some generosity of spirit, be described as common to all the multitudinous (but related) forms of life and, if so, potentially offer us guidance; perhaps, even, that firm place to stand. They are Awareness, Love, Creativity and Haecceity which, a little tongue-in-cheek, I call four Natural Duties. Underpinning these is the central activity of all living things, which Spinoza identified as ‘striving to persist in their own being.’ This is the existential context in which the duties operate.

A VERY QUICK INTRODUCTION TO THE NATURAL DUTIES

AWARENESS — Awareness is essential to even the simplest creature’s survival. The philosopher of science Peter Godfrey-Smith writes of ‘the windowed character of cellular life … All known cellular life, including tiny bacteria, has some ability to sense the world and respond to it.’ It must be aware of food and energy sources, predators, environmental changes, magnetic fields, signals from other creatures &c. Our privileged Western lives barely demand such sensitivity; we seemingly have no predators, and Sainsbury’s delivers everything. But if we are to live fully and exercise our haecceity (see below) we need to keep alert. ‘Attention,’ says Simone Weil, ‘consists of suspending our thought, leaving it detached, empty and ready to be penetrated by the object.’ We set aside preconceptions and out-of-date information to respond precisely to what is happening in front of us. Awareness respects the uniqueness of each moment. With it we can stay in reality with the rest of nature rather than slipping away into fantasy escapism, whether that be ‘reality TV’ or the stock-market.

LOVE — ‘Love is the perception of individuals... the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real.’ For Iris Murdoch and for STA, love is very close to awareness. We show respect to the creatures that surround us, knowing as we do from evolution that they are related to us and our equals. Those other creatures will not have evolved such nuanced understanding; nonetheless, their reluctance to engage in violence, except where necessary for survival, is a passive and rudimentary form of STA ‘love’.

(This may seem contentious; nature, as stated above, is amoral. It is not cruel; it is not sentimental. A cuckoo chick flinging its rivals out of the nest is obeying the imperative evolution dictates so that it may ‘persist in its own being’, the overriding context of existence. The animal behaviourist, Temple Grandin, cites examples of dolphins massacring porpoises for no yet apparent reason. Perhaps this is to be expected – dolphins have no moral code to deter them from such activity once they begin, but it is not, I think, their habitual behaviour. The Nazca boobies of the Galapagos frequently torment, rape and murder the chicks in the colony without any seeming ‘evolutionary advantage’ but this seems to be a horrific aberration or, as the researchers put it, ‘the first evidence in a nonhuman [society] of socially transmitted maltreatment directed towards unrelated young,’ abuse tragically much more familiar in our own society.)

CREATIVITY — can we call a donkey creative? Yes. Nature is creativity; all it does is make things. A donkey makes new cells in its body, it may make baby donkeys. It makes complex impressions in its brain out of millions of sensory stimuli, selecting those that will best clarify its experience in much the same way I’m choosing words here. The creativity that we admire in Botticelli or Stevie Wonder is essentially the same process we see in the cell-production in a blade of grass, the seed-production of a dandelion or a donkey’s ejaculation. It is only more elaborate because it is taking place in minds that have evolved greater complexity than these fellow ‘creatives’.

HAECCEITY (‘THISNESS”)1 — every creature is unique and 100% itself. Ornithologists say it is almost impossible to distinguish male and female swifts. What they mean is they can’t do it; swifts don’t have a problem. Male swifts are not continually trying to mate with other males (“’Ere, what’s your game?” “Oops, sorry, chum, my mistake.”) They can not only distinguish gender but individuals. They know that every swift has its own ‘thisness’, like every other organism. Haecceity is a biological fact.

(The four Natural Duties and their implications are examined in very much greater depth in the book STA published free online at sta-serial.com. Haecceity and Creativity will be the subjects of the July and September issues of The Familiar, Awareness and Love were partly explored in the first issue.)

If all creatures broadly observe awareness, love, creativity and haecceity, they do so unthinkingly and inescapably. We, for whom rational thought is now part of our haecceity, must use our highly evolved and educated intellects to adhere to the principles a slime-mould follows instinctively.

I don’t want to claim that this is a definitive moral system, rigidly observed by everything from sharks to sycamores. There will be exceptions, aberrations and lapses. These are informing principles rather than codes of conduct. Nature makes specific creatures, not laws; it is we who write the laws. If anyone of an analytical bent attempts forensic dissection of STA’s Natural Duties I imagine they’ll end up in a bloody mess, but if they try to live with them, I hope they’ll appreciate their value.

The Duties mix the personal and public. They show the relatedness of all things, and our uniqueness within that relatedness. Awareness and love involve social interaction; creativity and haecceity need not. But all are interconnected, informing and influencing each other. You cannot exercise your haecceity selfishly, or your creativity ostentatiously, if you’re aware of the myriad uniquenesses jostling around you which make a mockery of posturing ambition. You cannot let your awareness and love squash you into self-abasement so long as you observe the equal duties to create and exercise your own haecceity. Each situation calls out all the Natural Duties so that they remain in balance, the proper equilibrium of inward and outward impulses, individuality and relationships.

Alertness, an active respect for all living creatures, being ourselves, and making things. STA suggests that these are our duties in life. This is what the world (not to be confused with the media, who often describe themselves as ‘the world’) tells us we should be doing. As guidance rooted in reality and the pragmatism of evolution rather than social or religious ideas, it cuts clean through the matted tangle of ambitions and desires for made-up things – possessions, fame, hierarchy &c. It reminds us of the vastness of the context in which we live, where everything is connected, a world where each of our actions ramifies forever, where our haecceity means that we expand the universe with every new thought or sensation.

How much more exhilarating are these duties than our worries about ‘shoulds’ and ‘oughts’ and ‘better hads’ that furrow our brows and squeeze the blood in our hearts. An otter may get stressed by a shortage of fish, a dove by the presence of a peregrine; these are existential threats. But neither gets worried by forgetting someone’s birthday, or missing a deadline, or fuel prices, or by something somebody said. Their young will demand food until they’re old enough to find it themselves, but no one else piles any shit on their shoulders. Almost all our stresses belong to the world of attributed realities. That is not to say they are illusory, but they are not existential; to some extent they are chosen burdens. With a wider STA perspective, we may realise there are at least some we can do without.

The Natural Duties provide a deep awareness of all that is around us, the encouragement to express that appreciation creatively, and the sense of our uniqueness allied to the equal uniquenesses of all other creatures. This may sound ‘too good to be true’, but it is born out of a reality far deeper than our society’s current habits. I hope that it can help us ensure that what we do each day reflects who we are, rather than being behaviour imposed on us by peer pressure and the media.

Back in storyland in ancient Uz, Satan reckoned that Job was good only because he got so many perks from God. What is our motivation to behave well? Is it the tick-tock mechanism of reward/punishment? Or is it because, having stood still and considered the miracula all around us, we accept our place in the great order of things, and act accordingly? STA says the latter – in spite of jeering from the cynical cockpit of the media and those who pride themselves on being ‘realistic.’

We are part of a global, even cosmic, order, and all the advantages to be gained from selfishness and a defiance of that order are mere entertainments and attributed realities – status, celebrity, superfluous money, luxury – worthless tat we want only because the media and peer pressure tell us they are desirable. To rely on the media for our values is an abdication of our agency; to want what other people have is a failure of our selfhood.

The reason that such rampant, disproportionate consumption is seldom seen in nature is that it is unsustainable. Evolution (blind and ruthless as Justice) will not tolerate it for long and selects against it, shattering monopolies into diversity. Self-assertion, beyond what is needed for survival, is doomed. A Selfish Bastard may not care – he wants his private plane and sod the consequences to the planet. No ethical system in history has shamed everyone into decency. Our Selfish B would be undeterred by eternity in a fiery furnace or whatever karma might have up its sleeve; STA has no punishments to frighten him. Our motivation is not fear, it is consonance – the chance to ally with reality. The argument that he is disregarding the harmony of the universe is unlikely to persuade him. I can see that. Though his fantasies are the tired repetitions of media-stoked desires, he believes they are his own. He has his independence, and we have no authority. STA cannot coerce, it can only show and hope.

To send them all home happy, that ancient storyteller told his punters that God was appeased by Job’s repentance and, in a generous mood, doled out twice as much as before: a new family (to replace the one He had killed) with extra-beautiful daughters and 140 years of pious, prosperous, hearty old age. The proper fairy tale ending!

I cannot promise that if you make awareness, love, creativity and haecceity the guiding principles for your actions, you will earn yourselves 6,000 camels and a thousand she asses like Job – indeed STA deprecates such acquisitive ambition – but I do suggest (with Elihu and God) that stopping and reckoning with the wondrous things may be the best course open to us, individually and together.

THE RUDIMENTS OF STA

SEVEN STARTING-POINTS

So far as I can see, if we accept that evolution is true (and that the world is real rather than an illusion) and we ‘stand still and consider the wondrous things’ around us – the things themselves, not our words and ideas about them – then we logically end up with the starting-points I summarise briefly here (all worked out and explained in much greater detail at sta-serial.com):

1. Nature is real and the basis of our lives.

2. We are wholly involved in it and not separate in any way.

3. We generally ignore this affinity with nature, focussing on our own inventions (e.g., shopping, politics, football, TV etc) but …

4. ... a rewarding sense of belonging is available to us if we accept it.

5. Nature unceasingly creates new, unique individuals.

6. Nature is perfect, by definition; its only purpose being to do what it does (though this, of course, may not suit our personal interests).

7. As each thing is unique, all things must be equal; individuality-with-interdependence is the basis of relationships in nature.

There is some dispute about pronunciation, but with an OK from the OED, I say ‘heeksity’

This resonates deeply and I feel like it is a piece I will return to repeatedly to try to make sense of my ethics and spirituality. (A deeply religious friend once asked me “if there is no hell, then what stops people from doing horrible things?” And my response of “because we aren’t assholes and it isn’t fear keeping us in line” was insufficiently persuasive… and yet even to me there’s something more to it that I struggle to express.)

Also the perspective of “chosen burdens” is helpful. Instead of “I have to go to work” it becomes “I choose to go to work because I want to maintain my shelter/buy groceries/etc” and then I find myself asking questions like “what if I grew my own food?” Which is a very valid question, that can be answered quite resoundingly by my gardening efforts. But though the result is the same (I go to work), the latter is more comfortable to live with.

All that to say… thank you for this piece. And for explaining why I keep gardening and keep getting satisfaction from it despite results.