STA, the subject of these essays, is a reality-based world-view, which was summarised in the last Substack essay The World As It Is. Here I explore what I mean by a ‘world-view’, and why they seem to have gone out of fashion.

Why do we do the things we do?

Presumably, if we claim to have any control over our behaviour, it is because we think the things we think.

So, why do we think the things we think?

Are they what our schools or parents taught us? Are they the accepted views among ‘our tribe’? Do we merely think them unthinkingly? Are they the creed of a religion? Or what we’ve read in books or tweets? We are surrounded by cultural influences like these – we pick and choose from them as we might buy ingredients in a supermarket to cook up our own signature dish once we’re home. But it’s worth remembering that the goods carefully placed to grab our attention may not be the best quality produce.

I’d like to suggest a slightly different, home-grown rather than shop-bought, approach. I call STA a ‘world-view’. It’s not a word I like – too grand for something so simple – but ‘philosophy’ sounds pompous, and ‘paradigm’ is just horrible, so ‘world-view’ will have to do. Anyway, it emphasises that STA is based on looking at the world, this blue-green spinning planet and all the things that comprise it – water, stone, trees, people, armadillos, porpoises etc. We don’t find STA by conjuring up ideas, but by setting them aside and looking as innocently as we can at the real things in front of us. We start where we are – the physical us, our perceptions, instincts and intelligence brought to bear on this physical world – and gradually work out our values and eventually our actions from this direct experience rather than from things other people tell us (which is what education, religion, literature and the media are). It may be naïve to think we can shuck off all the cultural influences that bombard us, but in fact it’s easy to dispense with most of them and the effort itself is a bracing assertion of our direct, unmediated relationship with reality.

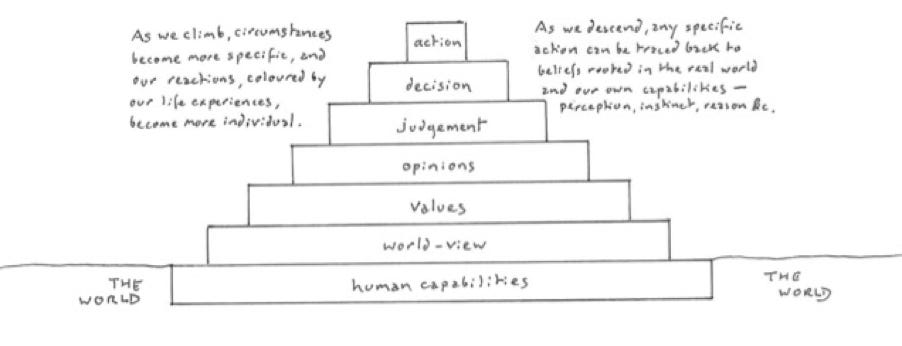

All of which is quite a mouthful and perhaps difficult to grasp without an illustration. Regular, patient readers of The Familiar will know my fondness for mildly silly, badly drawn diagrams, so behold......

THE ZIGGURAT OF CONSIDERED ACTION!

This is an ideal of how thought-fulness can work. Looking from top to bottom, you can see how any considered action relies on deep and broad foundations. It stems from a decision to act which in turn depends on a judgment. This has been influenced by a wider, less specific opinion which has been based on still more general values which finally are founded on a world-view, arising out of the nature of who we are and our experience of the surroundings in which we are embedded. STA is this world-view. At this basic level it looks at the world without social or cultural preconceptions and sees all living creatures as unique, interdependent and equal (because categories and hierarchies are later, intellectual inventions).

Climbing from the base, you can see how this world-view informs and underpins everything above it. The ziggurat also emphasises our commonality. Each of us is unique and individually circumstanced, but at this natural, most deeply rooted level of our human capabilities, we’re pretty similar, and if we start from this same footing, we won’t drift far apart. Nature, after all, is not the cause of our misunderstandings. Nature does not breed Russians and Americans, Hindus and Muslims, snowflakes and Sun readers; they’re cultural creations.

STA draws a clear line from what we know to what we do. If this sounds very simple, that’s because it is; if it sounds simplistic or too good to be true, it isn’t – it is, after all, the process by which every other organism operates. A daisy senses the sun and so opens its petals. We have evolved much greater complexity – the ziggurat has many storeys – but we can match the daisy’s directness, if not its immediacy. We can be complex without being complicated (as the composer Maurice Ravel liked to tell his students).

If all of this is as wise as I seem to be claiming, why is it not more widely followed? Society has always developed in a piecemeal, haphazard manner (and the disastrous attempts of those who tried to impose regularity like Stalin, Mao and Pol Pot, suggest it’s best that way), but the upheavals of the last century or so – globalisation, capitalism, technology – have come so fast and struck so deeply that we have struggled to assimilate them; instead, we have jettisoned any world-view in the chase to keep up. ‘We are trying to live without an agreed narrative of our place in the cosmos and in time,’ says Neil MacGregor. ‘Our society is, not just historically but in comparison to the rest of the world today, a very, very unusual one in being like that.’ He may be understating the problem. Many of us have no such narrative at all, let alone one we all agree on. We know that we have opinions, lots and lots of opinions, and we may have some values too, but we lack a coherent tale of how everything hangs together and where we might fit in.

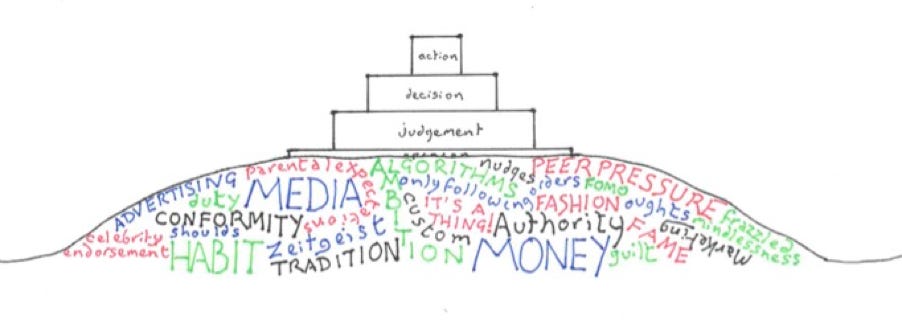

This is how the ziggurat looks today.

There are still opinions galore, but they rise out of a drift of acculturated rubbish. It’s hard to see the ancient path from what we are to what we do beneath this blizzard of doubts, distractions and delusions, which has blown in from all quarters – social, psychological, technological. There has always been clutter - tradition, money, ambition have been around for millennia, but the deposits have grown thicker and there are toxic new pollutants. Anyway, it’s unstable ground. Actions founded on this garbage are wholly unreliable.

This trash heap corrupts not only our private decision-making, but also our society and politics. The demagogues, tech bros and related vermin who have suddenly overrun the world live and forage in this litter. They are entirely ignorant of the connection of all living things; they have no idea there is solid ground buried beneath their scampering feet. They have no conception of depth. It’s easy to feel contempt for their nastiness, selfishness and vulgarity, but it is we who allowed the debris to pile up and so gave them a home. Trump was legitimately elected; Musk, Bezos, Zuckerburg only hold their power because we hand them the money to buy it. They are the creatures of our complacency.

Uninterested in anything but personal aggrandisement, they may be as ephemeral as a locust swarm but, even if so, we know they will wreak devastation in the meantime. How do we respond? STA et considera miracula – stand still and consider the wondrous things. The essence of STA is that we each make considered decisions for ourselves; it is not going to start preaching politics or prescribing behaviour. But whatever activism or quietism you think suits the situation, it will be most firmly built on the foundation of the ziggurat rather than trying to take root in the shifting detritus heaped about it. The loose litter is infested, but the Earth below is common ground and ours.

STA’s job is archaeological, clearing away the dross to uncover the citadel still standing strong beneath the muck At its foot lies our forgotten world-view with its reassuring firmity, so that we are not merely reflex-reacting to an agenda the vermin dictate, but behaving in accordance with who we are and what we know of this solid world and the fragile life clinging to it. I look at those snowdrops, that tree, my neighbour in his garden. I see them afresh: they are not resources, statistics, units of economic productivity. They are all unique creatures, inter-reliant, related to me, here together pursuing the privilege of living. And with this clear, well-founded understanding, thinking in harmony with the age-old, resolute earth, I can make my judgements, decisions and actions this beautiful spring day.

I don’t like to describe certain human beings as ‘vermin’, but the dictionary definition of the word is ‘small animals that can be harmful and are difficult to control when they appear in large numbers’, so it seems regrettably appropriate. Moths, flies, rats and cockroaches are part of the pattern of life, finding food and shelter, breeding, breathing, just getting by and doing their thing, oblivious to our squeamish distaste. The activities of Musk et al have none of that vital necessity. Of course, each of them is unique and objectively equal to any other organism – there are real human creatures beneath that absurd posturing – but they are intent on replacing our miraculous, multifarious reality with their narrow, destructive fantasy of money and futile power. Much more serious than their pantomime obnoxiousness, their fundamental understanding of life and the planet is wrong.

Ideally, they would all read my new book* and convert to a life of wonder, love and creativity, but I don’t think we can bank on it. So, we’ll need to explore other options, and the place to meet is the foot of the ziggurat.

( * or better books with a compatible world-view by e.g. Robin Wall Kimmerer, Annie Dillard, Charles Foster, Thomas Traherne et al.)

Your Lowly Hedgehog Knows takes a clear, fresh look at the physical world around us and finds it more startling and more heartening than the media would have us believe. Like the previous volume Do Not Call the Tortoise, Hedgehog offers a quietly revolutionary new/old perspective with the help of poets, biologists, woodlice, trees, John Lennon, cats (of course), a record-breaking vulture and, most of all, an openness to wonder.

It is published on May 8th. It will be available from all good bookshops, price £12. You can pre-order a signed copy which will be sent out a month in advance of publication here.

I’ll be talking about the book and STA in general with Owen Sheers at Hay Festival on Sunday 25th May at 8.30pm. Tickets are available from hay festival

A friend has a patch of woodland which she has been gently de-brambling with much the same conflicted thoughts on interfering with nature. Today I wandered along the path and enjoyed the display of bluebells that the space she has created has revealed.

That leads back to your item on art and creativity in that life itself is creative and "art" thrives anywhere that space is made for it.

Clear the dancefloor, weed the garden. Much the same thing.

I always want to leave a comment on these posts of yours because I like them so much. I regularly think about what you say about The Amazon being real and existing whether we acknowledge it or not, but Amazon disappearing if we cease to pay it attention. It’s very grounding.

What you say about our shaky foundation feels very true, and works well with Brian Klaas’s idea of a sandpile. His point is we’ve stacked the sandpile so high that any number of grains of sand added can bring the whole thing tumbling down. So again that concept of shaky foundation, though with a different message. Still, the solution is the same to both issues- we need to build a more solid foundation.

I can’t fix the world. But I can learn to move through it and see what is real and true and grounded. It is gradually changing my perspective. Like, my garden didn’t stress me out this summer. If I couldn’t pull all the weeds, well, “weeds” is a social construct. Without our societal lens, they are plants, with every bit as much right to grow in my garden as what I put there (more, even, as they are native species). Sure I still pull them to give preference to my chosen plants, but not pulling them is no longer a failure on my part.

Perhaps I’ve already told you this about the garden… it’s not easy to check… ah well. It’s all to say thanks, so there’s no harm in repetition.